Search this site

Climate Change, Drought, and Water Contamination: The Untold Story of California’s San Joaquin Valley

The Wellcome Photography Prize 2021 is free to enter and open for submissions. They’re looking for the human stories behind three urgent health challenges: mental health problems, infectious diseases, and global heating.

This year, they’ll award £26,000 to photographers covering three of the most pressing health issues of our time: Managing Mental Health, Fighting Infections, and Health in a Heating World.

To coincide with the call for submissions, Feature Shoot is highlighting groundbreaking work from photographers exploring these themes. In this story, we speak with Mette Lampcov, who has spent years documenting climate change and its consequences on public health.

“When I hear people talk about climate change, I often hear them ask, ‘When is it going to happen?’” the California-based documentary photographer Mette Lampcov tells us. “Well, it’s here. We are living it. And we’d better start looking it straight in the eyes.”

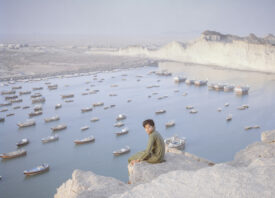

Lampcov’s ongoing project Water to Dust has taken her on countless trips across the state, where she’s borne witness to the devastation wrought by climate change. In 2018, she saw the aftermath of the deadly Woolsey Fire, which burned more than 96,949 acres. That same year, she photographed the death of 129 million trees amid California’s rising temperatures and drought. In 2019, she documented the story of the majestic giant sequoia trees, killed by bark beetles, a species made more dangerous by the climate crisis.

By 2050, climate change is predicted to cause 250,000 deaths annually, making it one of the most critical health issues of our time. Sea levels are rising faster than they have in millennia, and there’s more CO2 in our atmosphere than there’s been in millions of years. In the last twenty years, major floods have more than doubled, while severe storms have gone up by 40%. Climate change has also been linked to mental health issues like trauma, depression, and anxiety.

Lampcov focuses not just on the headline-grabbing issues like wildfires but also on the subtler underlying causes and repercussions of climate change and related issues. “As a photographer, I have decided that my job is to try to tell broader and more nuanced stories to help us understand the effects of climate change,” Lampcov says. “From the most complex stories to the simpler ones, they are all equally important.”

Still, perhaps no story underscored the human cost of our changing climate more than the one she found in the San Joaquin Valley, where resident farmworkers deal not only with drought but also contaminated water. In California, Lampcov says you can’t talk about climate change without talking about water–and vice versa.

“These stories are all connected, from the snowpack in the high Sierra Nevada mountains to our California drinking water,” she explains. Snow provides up to 80% of the state’s usable water, and residents rely on the Sierra Nevada snowpack to flow slowly and evenly throughout the spring and summer. When temperatures rise, the snowpack shrinks, and water supply suffers. “In our changing climate, this water source is very fragile, and supply and demand don’t match up,” Lampcov says.

The state does not have enough water, but its water issues do not affect everyone equally. In the Central Valley, the imbalance is compounded by water contamination, due in part to the surrounding “Big Ag” or factory farms, themselves a major culprit in global climate change. Lampcov learned about the situation through a contact; residents of the unincorporated towns of the San Joaquin Valley, most of whom are from communities of color and low-income communities, had to rely on allocated bottled water, as the tap water was unsafe.

Over one million residents in the San Joaquin Valley, many of them immigrant farmworkers, face the problem of contaminated drinking water. Many families deal with yellowish, foul smelling water that causes diarrhea, rashes, headaches. Some of the chemicals in the water are cancer-causing.

The water is most dangerous to children and older adults; PBS recently called it a “Silent Death.” “It was here that a mum told me she is left with no other option but to bathe her child in bad water, knowing it has chemicals in it,” the photographer remembers. “Here, people told me about how they know they are getting sick, but no one is listening to them.”

Although the water contamination itself isn’t directly caused by climate change, it is intertwined with the state’s water crisis; in areas like the San Joaquin Valley, there are fewer supply options for clean water. For the families living here, the situation means paying triple for water. First, they pay high prices to purchase the unsafe water. Second, they pay for safe but expensive bottled water, and third, they pay the high health costs associated with living with bad water. According to the Community Water Center, a non-profit clean-water group in the area, some families pay up to 10% of their income on water each month.

Many of these families are contact workers; for those making minimum wage and below, paying for the water they need to take showers, make coffee, and wash their clothes can become a significant financial burden. Lampcov saw the difficult working conditions in the area first-hand while documenting people working in the onion fields; picking and cutting onions by low light with sharp scissors from sunset until 11:00 PM or 12:00 AM, they make $1.30 for a sack of onions.

Many of these families came to California and put roots here to provide a better life for their children, but their futures remain uncertain. According to research from the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS), rural areas like the San Joaquin Valley will bear the brunt of continued climate change, as they’re more vulnerable to flooding and extreme heat. In California, the climate change issue is inextricably tied to questions of socioeconomic and racial injustice and inequality.

Lampcov is glad to know that people are talking more about climate change and water issues, but stories like these–from marginalized communities–still aren’t getting the attention they deserve. “These stories should be on the front pages of our newspapers,” she says. She’s interested in extreme events like wildfires and flooding, but she’s also concerned about the aftermath–the hidden, long-term effects of climate change that linger for months and years after the news and media have packed up and moved on.

We all have a role to play. “A little recycling is not going to change a lot at this stage, so what we need to do is put a lot of pressure on public officials and lawmakers.” The lack of safe and affordable water in the San Joaquin Valley is an urgent public health threat, and it also goes against the state’s Human Right to Water Bill.

Lampcov will continue working on Water and Dust for as long as it takes for people to start paying attention. “Just before I started, I had been accepted to a mentorship program at Anderson Ranch with James Estrin and Ed Kashi,” she says. “I thought this subject was a good fit for that three-year program, except I am still working on it, and three years is long gone.” The more she researches climate change and its effects on the state’s population, the more motivated she feels to persevere.

She doesn’t know what will happen to the families she met in the San Joaquin Valley, but their stories continue to inform her life’s mission. “When you care about the people you photograph and spend so much time with them, it affects you,” she tells us. “I see so much inequality, and I know many of the people I meet live hand to mouth.

“When telling these stories, I get to drive home once I am done, but they stay in a place where they know they will be exposed to unhealthy chemicals. During Covid, there is not a day that goes by that I don’t think about the people in those fields picking the food that ends up on our plates.”

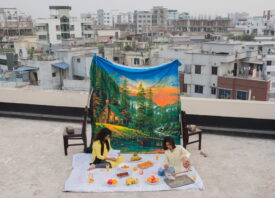

Wellcome, one of the world’s leading research-based charities, is looking for photographic work that sheds light on overlooked and unreported stories related to Health in a Heating World. This new theme is meant to draw global attention to environmental disasters reshaping our planet–as well as the people and communities working to prevent them.

They’re seeking images that reveal the human side of global warming while also advocating for international cooperation and collaboration during this crucial moment. As part of the Wellcome Photography Prize 2021, they’ll award an overall prize of £10,000, given to a series and single image winner; six nominees will also receive £1,000 each.

Feature Shoot Media has teamed up with the Wellcome Photography Prize to encourage photographers around the world to apply and make their voices heard on the most critical and urgent issues affecting our health, society, and planet. Submissions are open through January 18th, 2021. APPLY FOR FREE HERE.