Search this site

Shannon Johnstone on Creating Photos That Help Animals

Shannon Johnstone has photographed nearly two hundred at-risk shelter dogs at the Wake County Animal Center in Raleigh for her project Landfill Dogs. The photo shoots took place in North Carolina’s Landfill Park, known for its rolling green hills and crystal clear views of the city skyline–a paradise for dogs who spend most of their days in a noisy, crowded shelter. From Jumping Bean, the puppy who couldn’t sit still, to Bastian, the deaf dog who spent 84 days in the shelter system, each dog was one-of-a-kind.

They were also unwanted and overlooked. Johnstone has experienced both the grief and the joy that come with working with shelter dogs, watching some find families and seeing others die alone. She’ll never forget Weezy, who was euthanized inside a gas chamber at a shelter in another country, even as she raced to save him. She still thinks of Willie, who became depressed after living in the shelter for weeks before being adopted, at long last, following a fateful encounter in the park.

In 2017, Feature Shoot Founder Alison Zavos selected Landfill Dogs as one of the winners of the Feature Shoot Emerging Photography Awards. To coincide with this year’s open call for submissions, closing September 3rd, we asked her about her work on behalf of animals. There are still a few copies of Landfill Dogs, the book, available. Grab yours here.

You won the 3rd Annual Emerging Photography Awards for your project Landfill Dogs, a series of images celebrating some of the at-risk dogs available for adoption at the Wake County Animal Center in Raleigh, North Carolina. Can you tell us about the history of this place?

“I started Landfill Dogs in 2012 by asking my county shelter if each week I could take the dog who had been there the longest to Landfill Park. Landfill Park is a former landfill that has been converted into a public park. It was active for fourteen years, and it is now the second-highest point in the county. You can see for miles from the top, and it is beautiful.

“But the backdrop of Landfill Park is used for two other reasons. First, the dogs will end up in a landfill if they do not find a home. They will be euthanized and their bodies will be buried deep in the landfill among our trash. Below the surface at Landfill Park, there are more than 25,000 dogs buried. I think of this park as a burial ground. These photographs offer the last opportunity for these dogs to find homes.

“The second reason for the landfill location is because the county animal shelter falls under the same management as the landfill. This government structure reflects a societal value; homeless cats and dogs are just another waste stream. However, this landscape offers a metaphor of hope. It is a place of trash that has been transformed into a place of beauty. I hope the viewer also sees the beauty in these homeless, unloved creatures.”

How has this project evolved over time, and what does it mean to you today?

“Before I began Landfill Dogs, I thought it would just be a one-year project. I imagined a series of twenty photographs where we would see the seasons change, but the constant stream of dogs would be the same. However, as soon as I started the project, I realized that these images could help the dogs and perhaps even change their situation.

“We started a Facebook page that got a lot of media attention, and sure enough, dogs who had been previously ignored started finding homes quickly. I love this aspect of this project—it was an ongoing collaboration that asked the community to share the images and see if they could assist in helping these overlooked dogs. It cost nothing to participate, and any attention was good attention for these dogs!

As a photographer, communication is very important to me. I want my images to connect with people, and I want the photographs to be part of a conversation. Landfill Dogs was successful in this way, and it proved to be a positive (and productive) conversation about a difficult topic. In the end, 192 dogs from Wake County Animal Center were photographed. All but 22 dogs were either adopted or sent to rescue.”

Do you have any stories from Landfill Dogs that you’d be willing to share, from the grief to the hope you’ve experienced?

“In May 2014, I called the family that had adopted a dog named Weezy. I try to do follow-up photo shoots with all the families that adopt Landfill Dogs to show the dogs in their new homes. Unfortunately, in this case, the adoption had not worked out. After Weezy had destroyed some furniture, the family had taken Weezy to their local shelter in Davidson County.

“I feel a special connection to all the Landfill Dogs, so I needed to help him. After several phone calls, I discovered that Weezy was scheduled for euthanasia via gas chamber at the Davidson County shelter. The Wake County Animal Center, where Weezy had spent 194 days waiting for a home, agreed to take him back and give him another chance if I transported him.

“However, when I went to pick up Weezy in Davidson County, they brought out a different dog. In a case of mistaken identity, the wrong dog had been spared from the gas chamber. It turned out that Weezy had been euthanized days before, and the dog standing before me with a wagging tail was just a nameless stray dog who had never been claimed. Just one of the statistics. He was one of the some 200,000 animals destined to be euthanized in NC each year due to overpopulation.

“I named him Paco (nickname for St. Francis, the patron saint of animals). We made him a Landfill Dog in June 2014. He was adopted later in the summer and is now in a loving home. The people who follow Landfill Dogs even raised an additional $1000 for the adoptive mom to take him to dog training classes. This story illustrates the message I am trying to convey with Landfill Dogs. Every dog deserves a chance at a loving home. The shelters do the very best they can, but in the end, there are too many cats and dogs and not enough homes.

“People do not need to buy a pet from a breeder. There are good ones waiting at the shelter right now. If everyone did this, we could save all the Weezys and Pacos.”

How have you grown as a photographer since winning the Emerging Photography Awards? What have been some of your proudest moments in the years since?

“Winning this award definitely impacted my career, and it meant a lot to me not only because it affirmed the work, but because it demonstrated that these discarded and unwanted dogs have value and are worthy of our attention. Winning this award also connected me to like-minded curators and made me aware of a community of photography professionals whom I did not know.

“I think my proudest moment was at the panel discussion of the All Creatures Great and Small exhibition in Raleigh, NC in October 2019. The panel discussion was led by the amazing art historian Keri Cronin, and I remember sitting beside Jo-Anne McArthur, Traer Scott, and Lee Diedgaard thinking— ‘This is a historical moment. The talent and wealth of knowledge in this room are absolutely remarkable. I am surrounded by the greatest animal advocates and artists I know.’ I felt really proud.”

“Week after week went by, and Willie grew more despondent and detached. On March 31, we took him for his photo shoot. As we were walking Willie back to the car, a fire truck pulled up behind us and slowed down to turn into the trash drop-off site. For some reason, I asked if I could photograph Willie on the truck. They agreed, and I photographed him on the fire truck

“A few days later, as I was out running in the park, a guy recognized me and asked if the dog I photographed got a home. He told me his name was Dave and he had been the driver of the fire truck. He asked several questions about Willie’s history, temperament, and which shelter he was in. Dave told me that he had thought about Willie since the day we photographed him, and when he saw me in the park he said, ‘well, it was meant to be.'”

All Creatures Great and Small was a landmark exhibition exploring our relationship with animals, supported by the Culture and Animals Foundation and curated by Lisa Pearce. Why do you think more people have become willing to discuss our complex (and often broken) relationship with animals in recent years?

“This exhibition was very important for photography and human-animal studies for a few reasons. First, the exhibition featured six female photographers who all work in different facets of photography including photojournalism, commercial/editorial work, and fine art photography. These different areas and functions of photography are rarely featured together in a group exhibition.

“Secondly, this exhibition was unique because it depicted animals asubjects worthy of our moral consideration— in contrast to the way they are usually displayed, as objects, symbols, or tools used for human consumption, or at best, as a metaphor for something else. My goal is to try to change this. (For those who think this is really not an issue, I would like to point out two major portrait competitions: The Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition and the Taylor Wessing Prize, who do not allow nonhuman animals as subjects. This exclusion really speaks to the human-centric focus, and human exceptionalism that is prevalent throughout the photographic discipline).

“Since this exhibition was held at the college I teach at (Meredith College), it was important to me to offer our photography students examples of ethical animal representations across the different fields of photography. My hope is that we continue to offer exhibitions like this with community programming. It is especially important in agricultural communities, like the one I live in.”

“The photo shoot was in October (2013), just before Halloween, and I had been thinking about costumes and superheroes. While I was editing the photos, I noticed one of Jumpin Bean’s jumping photos looked just like Superman flying through the air. So I added a red Superman cape in Photoshop. Less than two weeks later, after Jumpin Bean had spent 123 days in the shelter, a young man, Brandon, came in to adopt him. Brandon said he was interested in adopting a dog that no one else wanted. I was incredibly touched by his compassion and selflessness.”

What other projects have you embarked on since 2017, and what are you working on right now?

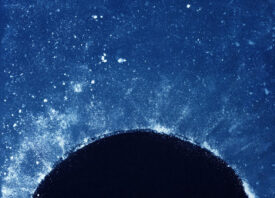

“Since 2017, I began a new project of cyanotypes made with the ashes of euthanized shelter animals. It is called Stardust and Ashes. I am currently working on two other projects; one follows animal control officers and tells the stories of the animals as they come into the animal shelter, and the other project is about roadside zoos. Both projects are in the beginning stages.”

The Feature Shoot Emerging Photography Awards are open for entries through September 3rd, 2021. Learn more here.